In early spring, as the snow melts and the earth thaws, the hearts of tiny frogs and salamanders who have lain in the earth over the winter also thaw and start beating. As these creatures warm up and start moving, they begin to pilgrimage toward the small seasonal pools where they themselves hatched in a previous spring.

Like a tent city that is transformed from an empty lot to a bustling metropolis within the course of a couple of weeks, a vernal pool rapidly morphs from a seemingly lifeless pond to a “grand central station” of the spring forest. Another name for vernal pools is “ephemeral pools” — so called because they are transitory and temporary.

As I learn more about vernal pools, I am struck by the fact that the lives of so many forest creatures intersect there and that they are so critical to the survival of so many species.

Maybe you’ve heard of upwellings in the ocean, places where cold nutrient rich water rises to the surface and — once mixed with sunlight –becomes a catalyst for an explosive growth of phytoplankton. The phytoplankton in turn supports a profusion of marine life including fish and sea birds.

Vernal pools and the creatures that inhabit them are the upwellings of the forest. The flow of nutrients they receive is in the form of the frogs and salamanders that return to them each spring in order to mate and lay eggs. These amphibians and their offspring are, in turn, food for a wide variety of forest creatures including turtles, snakes, ducks, herons, foxes, skunks, and raccoons. Like upwellings in the ocean but on a much smaller scale, vernal pools are nutrient powerhouses of the local food web.

Species that commonly inhabit Maine’s vernal pools include wood frogs, spotted salamanders, and fairy shrimp. For these creatures, the fact that vernal pools are by definition temporary is a deal-maker. In fact, without vernal pools, these creatures cannot successfully reproduce. The reason for this is that their eggs are gobbled up by fish, if fish are present. So a key to the survival of these creatures is laying their eggs in waters that do not have fish. Pretty smart, huh?

While frogs and salamanders are amphibious and can simply hop or crawl away from the vernal pool by the time it dries up in summer, fairy shrimp have no such option. Their solution is to have a short life span — and to lay hardy eggs that can survive heat, cold, and dry conditions until the pool fills up the next spring. How do fairy shrimp populations come to inhabit a pool far from others and high up on a hillside, one might ask? Turns out that the same ducks that feed on the adult shrimp inadvertently transfer shrimp eggs from one pool to another via their webbed feet.

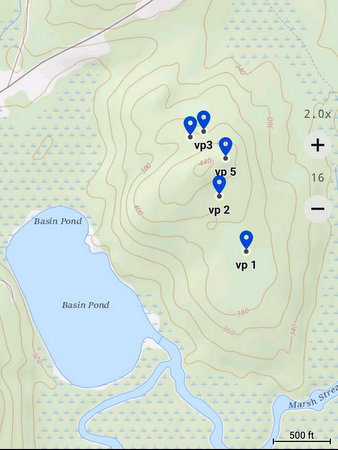

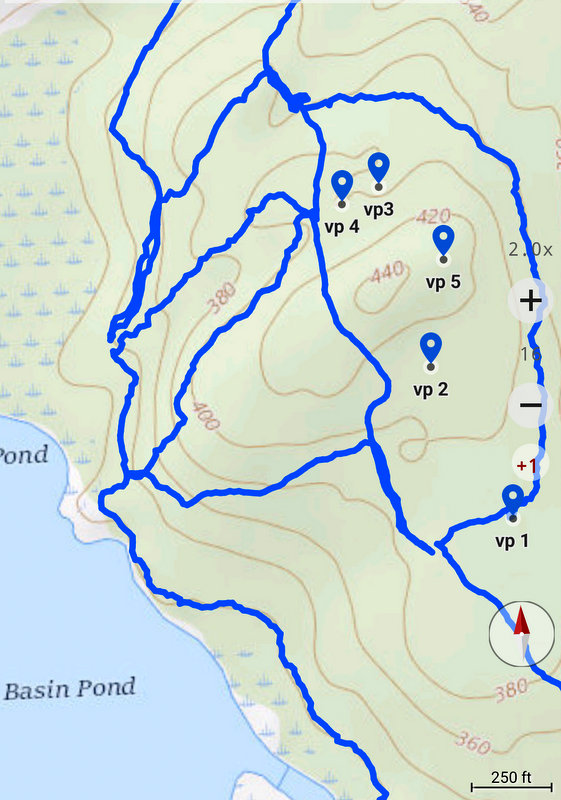

Want to see some vernal pools yourself? In this part of Maine, May is the perfect time of year to check for egg masses of frogs and salamanders. The town land at Basin Pond has five vernal pools that can be accessed off the Basin Pond Trail system. Hiking the trails and visiting the pools can be done in just a couple of hours and makes a great family trip. Maps and additional resources are below.

GPS Coordinates to Vernal Pools at Basin Pond in WGS84 Format

VP #1: 44.590083 degrees N, -69.066909 degrees W

VP #2: 44.591411 degrees N, -69.067816 degrees W

VP #3: 44.59297 degrees N, -69.068345 degrees W

VP #4: 44.592836 degrees N, -69.068796 degrees W

VP #5: 44.592325 degrees N, -69.067605 degrees W

———————————————————

Resources:

Basin Pond Trails — Printable Map (pdf format)

Fact Sheet: Vernal Pools (Maine DEP)

Significant Vernal Pool Habitat (Maine DEP)

The National Wildlife Federation: Wood Frog

Forest Ephemera: Vernal Pools

–Hearty thanks to Don Phillips of Phillips EcoServices for initially identifying and mapping these five vernal pools on the Monroe town land near Basin Pond.